Understanding Inflammatory Bowel Diseases (IBD)

Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis are the two main forms of inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), which affect millions of people worldwide. These chronic conditions pose a major challenge not only for those affected but also for healthcare systems. IBD is characterized by persistent inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract, and while the exact causes are still not fully understood, recent advances in medical research have shed light on the complex mechanisms underlying these diseases.

What happens in the gut?

Key players in the development of IBD include the immune system, the gut microbiota, the intestinal barrier, and various environmental factors. In healthy individuals, these components work together to ensure proper digestion and to protect the body from harmful pathogens. In IBD, however, this delicate balance is disrupted, leading to a misdirected immune response.

When the immune system goes astray

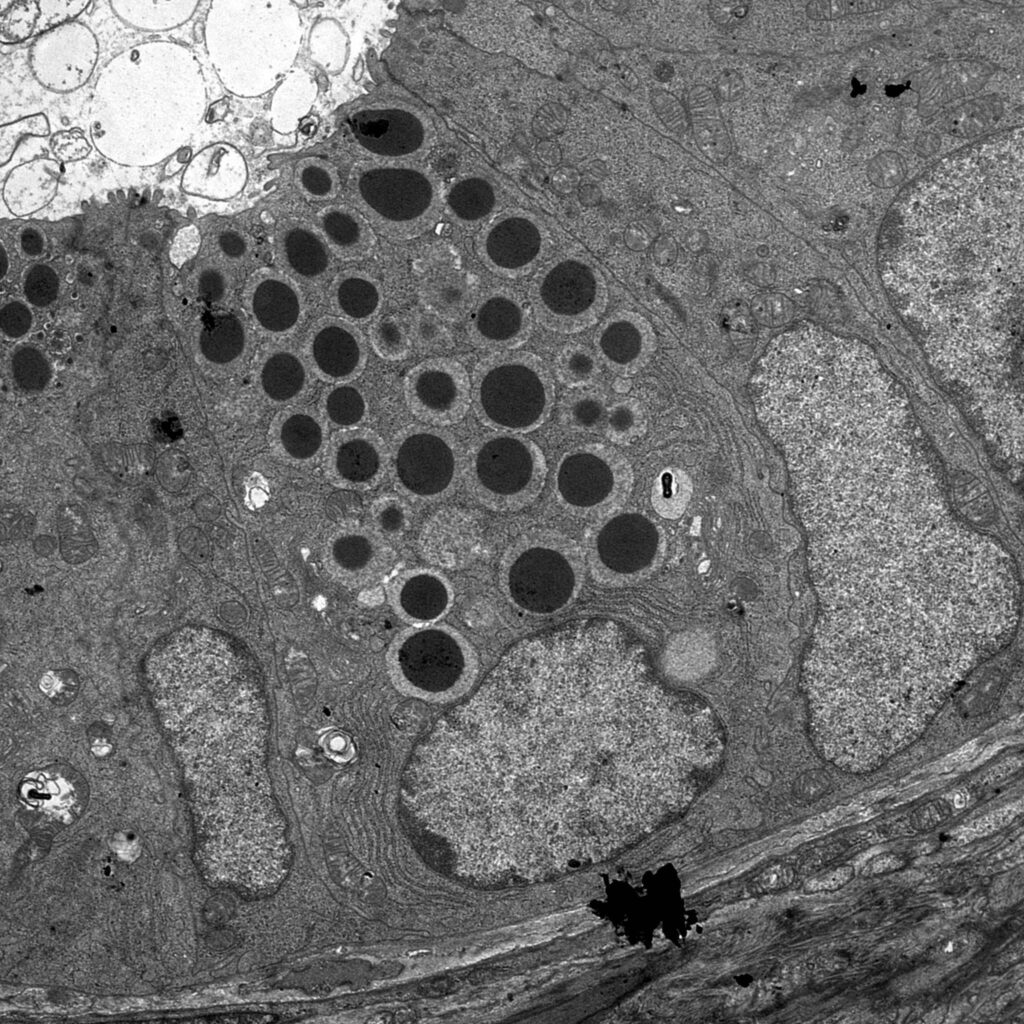

A large part of the human immune system is located in the gut, where it protects us from harmful microbes. In IBD, this defense system becomes problematic: instead of responding only to real threats, the immune system also attacks harmless or even beneficial bacteria, and sometimes the body’s own cells. This results in chronic inflammation, accompanied by symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, and weight loss.

The role of the gut microbiota

The microbiota – the diverse community of microorganisms that live in our intestines – plays a vital role in maintaining health. In people with IBD, this microbial composition is often altered, a condition known as dysbiosis. This imbalance can intensify inflammation and contribute to the progression of disease. However, it remains unclear whether dysbiosis is a cause or a consequence of IBD.

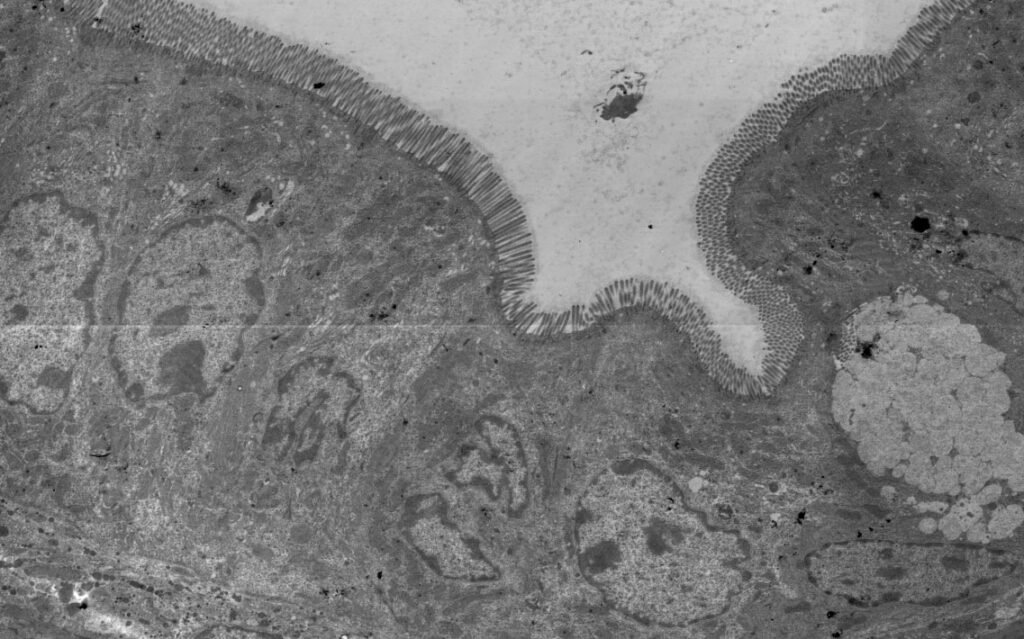

Damage to the intestinal barrier

Another critical factor is the intestinal barrier – a protective layer that prevents harmful substances and microbes from entering the body. In IBD, this barrier can become compromised, allowing bacteria and their components to penetrate the gut wall and trigger an immune reaction. This process can worsen inflammation and exacerbate symptoms.

Environmental influences

In addition to genetic predisposition, environmental factors also play a role in IBD. These may include diet, smoking, stress, and the use of antibiotics, all of which can impact the gut microbiota and influence the onset or course of the disease.

How Are Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis Diagnosed?

Diagnosing inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD), which primarily include Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, can be challenging. These conditions affect the digestive tract and often present with similar symptoms — such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, and weight loss — which can resemble other gastrointestinal disorders. A thorough diagnostic process is therefore essential to establish an accurate diagnosis.

Medical history and physical examination

The first step in diagnosing IBD involves a detailed conversation between doctor and patient (medical history) as well as a physical examination. The doctor will ask about the nature of the symptoms — for example, whether the diarrhea is bloody or not — and about abdominal pain, fever, fatigue, and any family history of bowel disease. These initial findings can offer important clues pointing toward IBD.

Blood tests

Blood tests are used to detect signs of inflammation in the body. These include elevated levels of C-reactive protein (CRP) and an increased erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), both of which can indicate active inflammation. Changes in blood count, such as anemia (low red blood cell count), may also be observed.

Stool analysis

Stool tests can detect markers of intestinal inflammation, such as calprotectin or lactoferrin, which are often elevated in people with IBD. Stool analysis also helps to rule out infectious causes of diarrhea.

Endoscopy

Endoscopy is a key diagnostic tool in IBD. During a colonoscopy, the entire colon and the terminal ileum (the last part of the small intestine) are examined using a flexible tube with a camera. This allows the physician to directly visualize inflammation, ulcers, or other abnormalities and to take tissue samples (biopsies) for further analysis. In suspected cases of Crohn’s disease, additional procedures such as an upper endoscopy (gastroscopy) or small bowel endoscopy (enteroscopy) may be required.

Imaging techniques

Imaging procedures such as ultrasound, X-ray, computed tomography (CT), or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are also used to further assess the digestive tract. These methods are particularly helpful in determining the extent of the disease and detecting possible complications, such as abscesses or fistulas.

Treatment of IBD: Managing Crohn’s Disease and Ulcerative Colitis

In recent years, the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) — including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis — has made significant progress. While a cure is not yet available, the main goals of therapy are to control inflammation, relieve symptoms, improve quality of life, and prevent long-term complications. With appropriate treatment, many people with IBD can live a largely normal life.

Medication-Based Therapies

- Treatment typically begins with medications that reduce inflammation and modulate the immune system. Common classes of IBD medications include:

- Aminosalicylates (5-ASAs): Drugs such as mesalazine (5-aminosalicylic acid), sulfasalazine, and others have anti-inflammatory effects. They are often used for mild to moderate ulcerative colitis but are less effective in Crohn’s disease.

- Corticosteroids: Powerful anti-inflammatory drugs used for short-term treatment of flare-ups. Due to their significant side effects, they are not suitable for long-term use.

- Immunomodulators: Medications like azathioprine, mercaptopurine, thioguanine, and methotrexate are used when other treatments are not sufficient or to reduce the need for corticosteroids.

- Biologics: These targeted therapies block specific molecules involved in inflammation:

- TNF blockers (e.g., infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab)

- Integrin inhibitors (e.g., vedolizumab), which selectively block immune cell migration into the intestinal lining

- Interleukin inhibitors such as ustekinumab (targets IL-12/IL-23) and mirikizumab (targets IL-23)

- These medications are especially useful for patients who do not respond to conventional therapies.

- JAK Inhibitors: Drugs such as tofacitinib and filgotinib inhibit Janus kinases (JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, TYK2), which are important for the transmission of inflammatory signals. By blocking this pathway, these medications help reduce immune system overactivation and inflammation.

The choice of treatment depends on individual disease characteristics. Your physician will work with you to develop the most effective treatment plan.

Nutritional Management

While no single diet suits all patients, tailored dietary changes can help control symptoms and improve nutritional status. For example, reducing intake of dairy products or high-fiber foods may benefit some patients. A balanced diet and, if necessary, supplementation can help prevent nutritional deficiencies.

Surgical Interventions

Surgery may be necessary in severe cases or if medical therapy fails. In ulcerative colitis, this may involve removing the entire colon (colectomy). In Crohn’s disease, surgery is used to treat complications such as strictures, fistulas, or severely inflamed sections of the bowel. The aim is always to preserve as much healthy bowel as possible.

Supportive Measures

- Smoking cessation: Smoking is a known risk factor that can worsen Crohn’s disease. Quitting smoking is an important part of the treatment plan.

- Psychosocial support: Living with a chronic disease can be emotionally challenging. Professional counseling and support groups can offer valuable help to patients and their families.

Why Research on IBD Matters

Research into inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis has significantly advanced over recent decades. These developments have deepened our understanding of disease mechanisms and led to more targeted and effective treatment options than ever before.

Understanding the Disease Mechanisms

A deeper understanding of how IBD develops is key to designing new therapies. Research has shown that IBD arises from a complex interaction between genetic predisposition, immune system dysfunction, environmental influences, and the gut microbiome. This knowledge has laid the groundwork for targeted therapies that intervene precisely in these pathways.

Biologics and Targeted Therapies

A major breakthrough in IBD treatment was the introduction of biologics — medications that block specific molecules involved in the inflammatory response. For example, TNF blockers (anti-tumor necrosis factor therapies) target a key cytokine involved in inflammation. These precise interventions allow for better disease control and remission while avoiding the broad suppression of the immune system. Ongoing research is essential to develop even more effective and better-tolerated treatment options. While many patients benefit from current therapies, others do not respond adequately or experience side effects. The continued development of novel biologics and selective inhibitors is a key focus of the Collaborative Research Center TRR241, aiming to deliver more personalized and effective treatments in the future.

Advances in Genetics

Genetic research has contributed greatly to identifying risk factors for IBD. Discovering genes associated with increased disease susceptibility has improved our understanding of disease origins and opened the door to personalized medicine. In the future, treatment plans may be tailored even more precisely to individual patients based on their genetic profile.

Microbiome Research

The study of the gut microbiome — the community of microorganisms in the digestive tract — has opened new avenues for IBD therapy. Research shows that imbalances in gut bacteria can contribute to inflammation. Approaches to modulate the microbiome through diet, probiotics, or even fecal microbiota transplantation are promising new strategies under investigation.

New Tools for Diagnosis and Monitoring

Scientific advances have also led to better ways of diagnosing and monitoring IBD. Non-invasive tests that detect biomarkers in blood or stool now allow for more accurate assessment of disease activity. This enables clinicians to adjust treatment earlier and more precisely, reducing unnecessary side effects and improving outcomes.